Don't call me Kiwi

Names matter, so we need to find the right ones.

Names matter, so we need to find the right ones.

On living without pretence in the wild world.

Selfies in front of Red Mountain or solitude for the wilderness explorer—which vision should prevail?

Wilderness, heritage and camembert.

A red-letter year for conservation continues to send ripples around the world.

Stewardship in the 21st century

Observing oystercatchers and remembering a life aquatic.

All is not great ’twixt the pond and the plate.

“We must talk again with trees,” wrote West Coast poet Peter Hooper. We must talk with them because we are apt to forget they are living beings. We think of them as timber sources and landscape features. Or as obstructions that stand in the way of a subdivision or block the kilometre-wide sweep of a centre-pivot irrigator... if we think of them at all. Despite this having been once a country of forests, there is no tree on the New Zealand coat of arms. There are a couple of fern fronds, but a cartoon Maori warrior and Pakeha woman are standing on them, like a mat (which is not a bad metaphor for how native vegetation has been treated in the past 150 years). Aotearoa was a land of giant trees as much as it was of giant birds. In both cases kauri and moa they were among the largest ever known. In the north, there is a story that the kauri tree has an oceanic twin, the sperm whale. It is an intriguing link, drawing on the fact that both produce resin ambergris in the sperm whale and the skin of both flakes off in thick slabs. And the size, of course. Imagine you’d stepped off a waka after crossing the Pacific, serenaded by singing whales, and were confronted with a six- or seven-metre-diameter kauri trunk. What would come to mind? Kauri are the rangatira tree of the north, but south of their natural range (which cuts off around the latitude of Raglan), that chiefly role is taken up by totara. During my travels for the forests story in this issue, I visited one of the rakau rangatira of Pureora State Forest. It has a name the Pouakani totara signposted on the main road. I parked and took the 20-minute walk to the tree, on a track that weaved through agreeably dense bush. Halfway along, I paused beside a fallen totara log to inspect a pile of wine-red shavings, the work of chewing insects and other agents of decay, rendering the trunk into nurture for life underground. About the time I thought I must be close, I glanced to the right of the track and thought for a moment I was seeing an outcrop of rock. Then my knees went weak and something buckled within me. According to Greek history, the Persian king Xerxes the Great once saw a majestic plane tree during the course of a military march. He halted his army and ordered that they set up camp around the tree so that he could admire it. The historian Aelian recorded that Xerxes “attached to it expensive ornaments, paying homage to the branches with necklaces and bracelets. He left a caretaker for it, like a guard to provide security, as if it were a woman he loved.” That is how you respond to a chiefly tree! I walked around a fence that had been erected to protect the totara and looked up into its plant-drenched canopy. This tree began its life 1800 years ago, around the time that Taupo erupted and flattened the central North Island. This tree precedes all human life in Aotearoa. Yet totara is the timber that Europeans dignified by turning it into window sashes, doorstops, foundation piles and fenceposts. From today’s perspective, it seems as lamentable as using Chateau Lafite in a stir-fry. How the Pouakani totara escaped the chainsaw, I do not know. But had protesters not taken to the Pureora treetops in 1978, all this would surely be gone. The illustrious ornithologist Charles Fleming said New Zealand’s podocarp remnants are this nation’s Gothic cathedrals, and standing in the presence of a tree like the Pouakani totara is an inescapably numinous experience. The ancients understood this. Pliny the Elder wrote: “As much as we adore the statues of the gods, with their brilliant gold and ivory, we revere the forests, and the silences within them.” In Maori understanding, trees are part of the human family tree: they are our elder siblings. Tane, they say, made trees before making humans a story not dissimilar to the first chapter of Genesis, or to the unravelling of the human genome, which shows we share a third of our genes with oak trees. It is said you can’t know who you are until you know where you are. Kentucky farmer and essayist Wendell Berry wrote: “Until we understand what the land is, we are at odds with everything we touch. And to come to that understanding...we have to re-enter the woods.” We must talk again with trees.

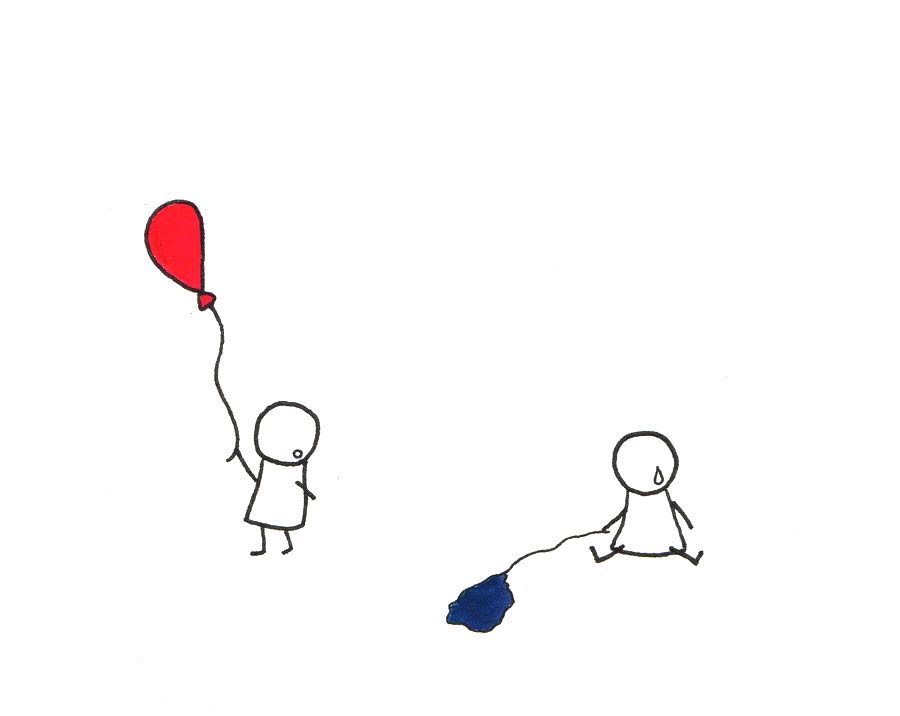

Connection in an age of fragmentation.

When Te Warihi Kokowai Hetaraka stood before the Waitangi Tribunal at Panguru, North Hokianga, in 2010, he was the embodiment of the past speaking into the present. He wore a feather cloak and gave his evidence holding a greenstone mere, and although he spoke in English, his subject was Maori to the core. He addressed the reliability of oral history, on which Maori claims for justice rely. When the Declaration of Independence was signed in 1835, te reo Maori had been a written language for only 15 years. Unsurprisingly, there are very few Maori written sources from that period, but a rich vein of korero exists concerning the intentions and expectations of the signatories. How much reliance can be placed on that testimony, based as it is on memory and verbal transmission from one generation to the next? This is the $64 million question. Or, rather, $170 million, or $300 million, or whatever figure the Ngapuhi claim may be settled for. It was also a question that nagged me as I attended several days of hearings over Ngapuhi’s sovereignty claim, about which I wrote in a feature in this magazine. As one who struggles with memory—mine seems to be a colander with ever-widening holes—I came to the hearings with the standard Western preference/prejudice for the permanence of the written over the transience of the oral. Hetaraka, a master carver, confronted the legitimacy of that view by referring to his practice of whakairo. He spoke about the intense tapu that surrounds working in timber. Trees are the domain of Tane-nui-a-Rangi, the giver of life, he said. “A tohunga whakairo must therefore navigate the transfer of the superior wairua and the mauri connected to the tree to a new form for human use, and tapu must be strictly observed. There must be no mistake in the whakapapa recitations from Ranginui and Papatuanuku so as not to imperil the project and the people involved.” In the Maori world, knowledge is not to be trifled with, and its transmittal is never haphazard. I recall stories of Dame Whina Cooper, herself from Panguru, being drilled in whakapapa as a child, going over and over the names until they became chiselled into memory. Another speaker at Panguru said that much of her learning took place in Waipoua Forest at 3AM, when the spirit of the forest was strongest and the veil between past and present thinnest. To Ngapuhi, the strictness of whakapapa ensures the reliability of oral history, and the guardianship of that history is a sacred trust. Indeed, the phrase “chiselled into memory” takes on a new meaning when you consider that the chisel is the pen of the Maori people—on skin, on timber, on memory. I was struck by the statement of one Ngapuhi, contradicting the view that Maori was an exclusively oral culture. “Whakairo was our written language,” he said. Carving wrote the symbolism that describes the cosmos. For Maori, oral history fits within a world view that sees no separation of knowledge from lived experience, or history from memory. The Waitangi Tribunal itself has accepted the principle that communal memory holds knowledge that can be found in no other way. In its landmark Muriwhenua report in 1997, the tribunal wrote that its “greater concern” was not so much “with the vagaries of oral tradition, but with the power of the written word to entrench error and bias”. Yet the Eurocentric bias persists, a vestige of the hierarchical thinking that blighted our nation’s beginnings. Settlers, administrators and missionaries alike placed European culture high above that of indigenous people. Still today there is a privileging of the ‘evidence-based’ scientific paradigm over all others. Naturally enough, colonised people the world over repudiate that prejudice. Davi Kopenawa, a leader of the Yanomami people of the Amazon, has said that white people fixate on the written word “because their thought is full of forgetting”. By contrast, “we have kept the words of our ancestors inside us for a long time and we continue to pass them on to our children”, he says. In 1840, when Hokianga rangatira Hone Mohi Tawhai was deliberating whether to sign the Treaty of Waitangi, he said to the Pakeha who were gathered at Mangungu: “Let the tongue of everyone be free to speak; but what of it? What will be the end? Our sayings will sink to the bottom like a stone, but your sayings will float light, like the wood of the whau tree, and always remain to be seen. Am I telling lies?” He was not. His prediction has come to pass. Several Ngapuhi elders at the hearings said that this was the first opportunity they had been given to present their stories to the Crown in full. Ngapuhi see this claim as a way to lift their suppressed history—so long invisible—to the surface. To let it speak.

. . . and why it continues. The view from 25.

What was learned from New Zealand’s worst canyoning disaster?

Editor-at-large Kennedy Warne considers the place of poets as stewards of landscape

Loading..

3

$1 trial for two weeks, thereafter $8.50 every two months, cancel any time

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Signed in as . Sign out

Ask your librarian to subscribe to this service next year. Alternatively, use a home network and buy a digital subscription—just $1/week...

Subscribe to our free newsletter for news and prizes