A matter of principles

Misinformation about the Treaty of Waitangi, its language and its intent is at the centre of the Treaty Principles Bill introduced to Parliament this week.

If I could travel back in time, I’d visit England in 1820, when two Māori rangatira met the newly crowned British monarch, King George IV. Hongi Hika and Waikato had travelled to Britain with missionary Thomas Kendall to help create the first Māori-English dictionary.

The king welcomed his Ngāpuhi visitors in the throne room of his London residence, Carlton House. Waikato and Hongi (rendered “Shunghee” by the British) greeted the king with the words: “How d’ye do, Mr King George?” to which the king replied, “How d’ye do, Mr King Shunghee? How d’ye do, Mr King Waikato?”

The King of England then gave the antipodean kings a tour of the palace, showing them its stately gardens, lavish art collections, sumptuous interiors and—of most compelling interest to Hongi, a veteran warrior—its armoury, bristling with exotic weapons. Hongi and Waikato gave the king the finely woven cloaks they were wearing. (The mana of a garment that has been worn by a rangatira is immeasurably greater than that of a newly woven garment.) In return, the king gave Hongi a coat of chain mail, the helmet from a suit of armour, and two muskets.

What I find compelling in this face-to-face exchange between Māori leaders and the British king is that it assumed a relationship of equal standing between sovereigns and set a tone of mutual respect and reciprocity between the chiefs and the monarchy—one that would endure for the next 20 years, through the signing of a declaration of independence by northern chiefs, the choosing of a national flag and, ultimately, the negotiation of a treaty.

Then it all went to the dogs. The political recognition and cultural respect accorded to Māori by the British Crown was withdrawn and submerged under a rising tide of prejudice, denigration and injustice that prevailed for a century.

[chapter-break]

The past 50 years, a modest renaissance to the previous dark ages, have seen a gradual recovery of recognition and political standing for Māori. That renaissance ended with the introduction of the Treaty Principles Bill on November 7. The Waitangi Tribunal describes the bill as the “worst, most comprehensive breach of the Treaty/te Tiriti in modern times”.

Dressed in the language of non-discrimination, national unity, equal rights and “one law for all”, the bill seeks to nullify the Crown’s formal relationship with Māori. Its aim: to create a country that has dispensed with its obligations to its indigenous people and that frames itself as ‘Kiwi, not iwi’.

The Bill portrays the treaty not as a treaty for Māori but for all New Zealanders, Māori and non-Māori alike. This doesn’t make sense: in 1840, the term “New Zealanders” was used exclusively for Māori and never for Pākehā. Māori—at that time 98 per cent of the population—were self-evidently the people of Nu Tireni, the islands of New Zealand; they were New Zealanders. When the term appears in the treaty, it is referring to Māori.

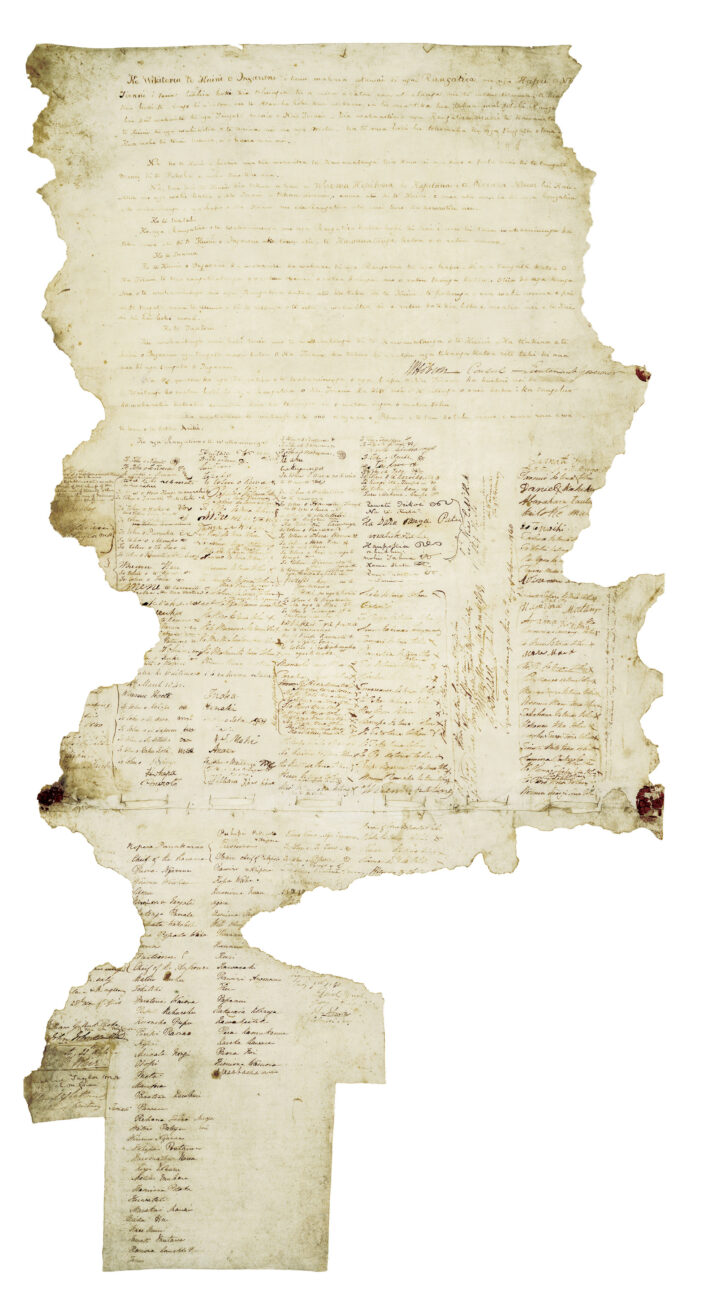

The context in which the treaty was made also defeats the “all New Zealanders” argument. The treaty was designed for Māori, delivered in Māori, discussed in Māori and signed by Māori. The fact that there were a few Pākehā bystanders present at the signing is irrelevant. The treaty was not for them. So when the treaty refers to “all the people of New Zealand” it is saying that this document is not just for the chiefs doing the negotiating, it is for all their people.

[sidebar-1]

A more audacious revision is the Bill’s rendering of the crucial second article of the treaty and its guarantee of tino rangatiratanga—supreme authority—to all Māori. According to the Act Party, the promoter of the Bill, the second article is not a promise to signatories to protect their chieftainship over lands, villages and all their treasures; rather, it is a promise to all inhabitants of these islands “to flourish in self-chosen ways”, as leader David Seymour puts it.

This is re-writing the text of the treaty. First, tino rangatiratanga does not mean “the right to flourish”. It means chiefly authority possessed by and guaranteed to Māori by virtue of being Aotearoa’s indigenous people. Second, tino rangatiratanga is a Māori concept that belongs to Māori and was guaranteed to Māori as part of a treaty that was negotiated with Māori, and no one else.

It also renders the agreement as one between “races”.

Except that the treaty is not about race. The historic reality is that the treaty was not negotiated between two races but between two sovereign peoples. The word “race” is not used in the treaty, nor was it mentioned in the deliberations leading up to its drafting, nor in the discussions with chiefs that preceded its signing. The word was not used because race was not relevant to the matters under consideration. The contract that was transacted at Waitangi, and at all the subsequent sites where the treaty was signed, had to do with peoples, not races.

Te Tiriti is not a treaty between Māori and British “races” any more than ANZUS is a treaty between the Australian, New Zealand and United States “races”. They are political agreements between peoples.

Race-baiting continues to be an effective tool for politicians. “Racist” is a totemically powerful accusation, and the assertion that someone is benefiting on the basis of ethnicity is guaranteed to inflame resentment, and resentment is the fuel of populism.

This is exactly what is happening. Reparation for the injustices of colonisation is labelled “special treatment on the basis of race”. To claim, as Seymour does, that support for Māori empowerment indicates “a corrosive obsession with a person’s race” is a reversal of reality. Rather, it demonstrates a constructive quest for justice.

There is another reason why it is politically profitable for populists to frame the treaty as a race-based document. Indigenous peoples possess internationally recognised rights by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, including a right to self-determination; races do not.

Populist politicians will push back against any acknowledgement of Māori collective rights and insist that individual rights have supremacy. Why? Because treaties are not subject to conventional democratic principles of individual rights and non-discrimination.

Pākehā are not a party to the Treaty of Waitangi. The treaty “contract” is between Māori and the Crown, and the rights guaranteed to Māori under Te Tiriti cannot be limited by the rights of other citizens. Rather, it is the opposite. As the Privy Council has stated, the Crown took on the responsibility of protecting and preserving Māori property “in return for being recognised as the legitimate government of the whole nation by Māori”.

As history records, the Crown completely failed to protect and preserve Māori property. Indeed, the Crown was the primary agent of the alienation of that property. Not surprisingly, Māori, along with other indigenous peoples, have persistently challenged the legitimacy of settler governance.

[chapter-break]

Kirsty Gover, a New Zealand professor at Melbourne Law School, writes that indigenous peoples have a right not just to participate within a given constitutional framework, but to be empowered to negotiate the design of those constitutional arrangements. This is fundamental to the idea of self-determination.

The idea that indigenous people should have rights not possessed by the rest of the populace does not fit with the universalist vision of equal rights for all—especially in regard to issues of governance of resources (such as water), political representation (such as Māori wards) and the exercise of sovereignty.

“Either New Zealand is to be a liberal democracy where all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights, or a kind of ethno-state where some are born more equal than others,” says David Seymour. This is a false dichotomy. It is not one or the other. It is, in fact, neither. Individual New Zealanders do indeed have equal rights. But by virtue of being indigenous and possessing guarantees of self-determination via Te Tiriti, Māori collectively have additional rights.

The assertion that this makes Māori “more equal” is abursd. On every social indicator Māori as a group are less well off, less “equal” than non-Māori. So too is the suggestion that the country could become a state dominated by the interests of Māori. If anything, the threat of ethnocracy comes from the other direction: nationalist movements which envision a white ethnostate as the ideal.

New Zealand is not alone in addressing the challenge of indigenous sovereignty. Other settler nations (Australia, Canada, the United States) face the same issue: that common citizenship and equal participation in democratic processes do not achieve the self-determination to which indigenous people aspire.

The reality, as Canadian political philosopher Duncan Ivison and colleagues point out, is that egalitarian political theory typically ends up justifying explicitly inegalitarian institutions and practices.

The challenge, then, is formulating a political structure that is built on a just relationship with indigenous peoples. No easy matter, when, as Ivison and his co-authors write, “most states owe their existence to some combination of force and fraud”. Given that repressive history, the issue is how the state can become “morally rehabilitated”.

Which invites the question: Does the state even wish to be rehabilitated? Typically, it does not. Settler states are reluctant to accept that Indigenous people have a legitimate role in determining the constitutional order.

In most parts of the world Indigenous peoples are minorities, and are therefore unlikely to achieve electoral outcomes that reflect their interests. The nature of settler society, adds Australian political philosopher Paul Patton, virtually guarantees that Indigenous people remain “consistently and systematically on the losing side in majority decision-making processes”.

[chapter-break]

Supposing there were a willingness to embrace constitutional reform and acknowledge Indigenous sovereignty, what would a just relationship between the Crown and Māori look like? The much-admired constitutional lawyer and Indigenous rights expert Moana Jackson spent years working on a blueprint for constitutional reform that would achieve justice and show fidelity to the Treaty as part of a collective known as Matike Mai Aotearoa, the Independent Working Group on Constitutional Transformation. The group spent five years travelling the country and listening to what Māori had to say on the subject before publishing its report in 2016.

Matike Mai insisted that constitutional change must happen. The history of Māori subjugation under colonisation requires it, they said. So do the terms of the treaty.

“Perhaps more than anything else the discussions we have been part of were shaped by the often bitter experience many Māori people have had and continue to have in dealing with the Crown,” the group wrote in its report. “Together they have engendered a very firm belief that the Westminster constitutional system as it has been implemented since 1840 does not, indeed cannot, adequately give effect to the terms of Te Tiriti.”

According to Matike Mai, a large part of the bitterness Māori experience in their dealings with the Crown derives from the incorrect assumption that Māori ceded sovereignty.

The working group pointed out that the fact that there is no word for “cede” in te reo “is not a linguistic shortcoming but an indication that for the rangatira who signed Te Tiriti, to even contemplate giving away mana would have been legally impossible, culturally incomprehensible, and politically and constitutionally untenable.”

The chiefs did not give away their mana, but it was taken from them anyway. And here lies the nub of the constitutional conundrum. “For the discussions ultimately raised the profound question of whether a State built upon the taking of another people’s lands, lives and power can ever really be just or treaty-based if it maintains a constitutional order that was part of the taking,” wrote the working group. “It was a recognition that in the end a full and final ‘settling’ of colonisation should mean more than a cash payment and even an apology. It requires a transformative shift in thinking to properly establish the constitutional relationship that Te Tiriti intended by restoring the authority that was once exercised through mana and rangatiratanga.”

Matike Mai mapped out possible pathways for shared governance. Just as the existing legislative, executive and judicial branches of government have differing spheres of influence, so too would Crown and Māori define their own spheres. But progress along this road seems largely stalled under the current government.

There is a question of honour here, acknowledged by the late Queen Elizabeth in a speech she gave at Waitangi during the 1963 royal visit. “Whatever may have happened in the past and whatever the future may bring it remains the sacred duty of the Crown today as in 1840 to stand by the Treaty of Waitangi, to ensure that the trust of the Māori people is never betrayed.”

Māori have been appealing to the government to “honour the treaty” for as long as I can remember.

Seymour has said that Act’s Treaty Principles Bill will give all New Zealanders “the same respect and dignity, including equality before the law”. But by opposing Māori indigenous rights, the Bill fails to give respect and dignity to Māori. More than that, the Bill has no ultimate relevance because the treaty is a contract between Māori and the Crown, and the opinion of the rest of the population about its meaning can’t alter that fact. It lies outside the scope of democratic influence.

[chapter-break]

A device populist governments use to deal with the “problem” of indigenous sovereignty is to eliminate the category of indigenous people altogether, by declaring that “we are all indigenous”. Politicians of all persuasions have an interest in denying indigeneity. If we are all “indigenous” then the claims of a specific group claiming indigeneity can be dismissed.

In 2004, in a speech entitled “We are all New Zealanders now,” former Labour MP (and later Speaker of the House) Trevor Mallard said that the 21st century should be about “banishing the demons from our past, cheering each other on as New Zealand citizens, and being successful”, because “Māori and Pākehā are both indigenous people to New Zealand now”.

Commenting on the speech, Ani Mikaere, who teaches Māori law and philosophy, said, “Just as Brash continues to cultivate a coalition of the fearful, it is equally plain that Mallard is intent on forging a coalition of the forgetful: Māori must forgive and forget, and Pākehā must be allowed to forget, so that we can all live together as one big, happy, amnesic family.”

For Mikaere, forgetting is not an option. A determination not to forget is at the heart of living as an indigenous person, she says. “Māori understand only too well our obligation, to generations past and future, not to forget.”

Here, the coalition government is in a bind. Act’s leader follows the “we are all indigenous” line, but his coalition partner, New Zealand First leader Winston Peters, takes the opposite tack: that no one is indigenous. We are a nation of immigrants, he argues, and the length of time we have been present is irrelevant. “I want everybody in this country, no matter whether they’re here for 1000 years or here yesterday, legally to be treated the same, equally as one people,” says Peters.

Alice Te Punga Somerville, a professor of indigenous studies at the University of British Columbia, points out that the “Māori aren’t Indigenous” claim simultaneously invokes two different myths: that Māori weren’t the first arrivals (the long debunked “Moriori were here first” myth), and that Māori are not substantially different from anyone else who has arrived here since (the “nation of immigrants” myth).

There’s a reason that indigenous peoples are also known as “first nations”. This is not to deny later arrivals a sense of belonging to a place, of bonding to the land. That pathway is available to all and should be embraced by all. But indigeneity is a unique phenomenon. The people who became Māori had their existence shaped by an encounter with these islands that is unrepeatable.

“No other group of people in New Zealand’s social history will have such an opportunity of developing a oneness with the soil as Māori did in transition from their East Polynesian origins: being born out of and returning to Papatūānuku in a closed cycle of renewal and decay which moulded their thinking and being from that time onwards,” writes scholar and author Ailsa Smith.

“It’s not really obvious why some people’s background is more important than others,” Seymour opines. . “I’m not really sure why we take a period of time 200 years ago and decide to privilege some humans over others.”

Yet it’s not the mystery Seymour makes it out to be.

What the treaty guaranteed to Māori was not just democratic participation, like all other citizens, but also a say in the design and establishment of the constitutional order. This was denied to Māori in the aftermath of 1840 and continues to be denied to them today.

It is also disingenuous to pretend that the origins of Māori political claims are merely “a period of time”—an apparently arbitrary moment plucked from the hat of history. These claims arise from a specific event: the signing of Te Tiriti. The treaty is a record of a transaction that occurred on a certain day in a certain place between two sovereign entities.

I began this essay by recounting an historic meeting between “kings” of Aotearoa and the king of England. One of the most significant meetings of my life occurred in 1989, when I met kuia Saana Murray of the Far North iwi Ngāti Kuri, and worked with her on a story for the second issue of New Zealand Geographic. (I wrote about Saana here and here.)

A few years later, Saana was one of six iwi representatives who lodged a claim concerning Māori culture, knowledge and identity with the Waitangi Tribunal. Saana cared deeply about Māori knowledge—mātauranga—and believed that tangata whenua are its rightful and necessary custodians. She believed that the Treaty of Waitangi guaranteed the custodianship of Māori things by Māori people, and it pained her that that guarantee had not been honoured. Yet Saana never stopped believing in the Treaty.

“I was born to the tune of the Tiriti of Waitangi,” she wrote. It was a tune she would sing all her life.

Though I met her only briefly, I knew I was in the presence of someone for whom honour ran deep. There was honour in knowing that one’s ancestors had put their mana on the line and signed up to a political relationship with the British Crown. As a descendant, Saana felt honour bound to fulfil her role as an upholder of treaty principles and, as she put it, being the “Great Objector” when those principles were breached. She had spent her life in service of her people because her dying mother had asked her to promise to “retrieve the land and ratify the Treaty”. Land and treaty were the wellsprings of Saana’s energy and passion.

I contrast the integrity and honour I saw in Saana with the meanness I see in the rhetoric and policies that undermine the treaty and deny honour to the indigenous people. There is plenty of talk about equal treatment, but none at all about equal justice.

It is the memory of Saana that makes me want to align myself with the indigenous struggle and not to mouth the platitudes of the one-nation crowd. I choose to sing Saana’s tune.