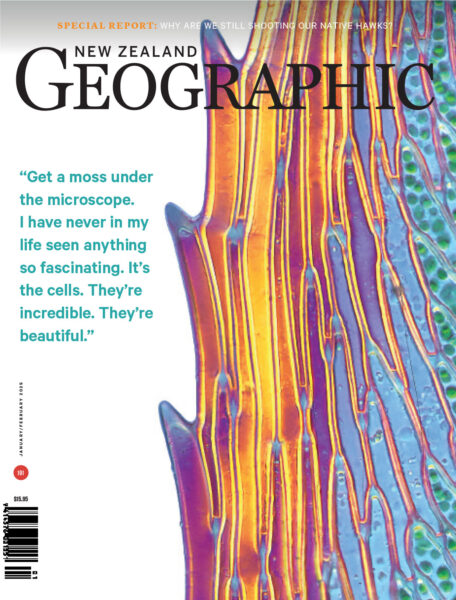

Perception & reality

The other morning I set a deeply unimpressive personal record. The drive to work, which usually takes 45 minutes, stretched out to an interminable 77. I sat at one intersection for more than half an hour, listening to my emails ping and wondering how I fell into this trap. So, I suspect, did everyone around me.

Going car-free is the single most powerful thing a person can do to mitigate climate change, according to data published by global research company Ipsos for Earth Day 2024. That, for my family, feels impossible. Likewise, we can’t afford to switch to an electric vehicle—the second-most powerful lever on the list. (The third, though, is a cinch. Ditch one long-haul flight? Done. I hate flying.)

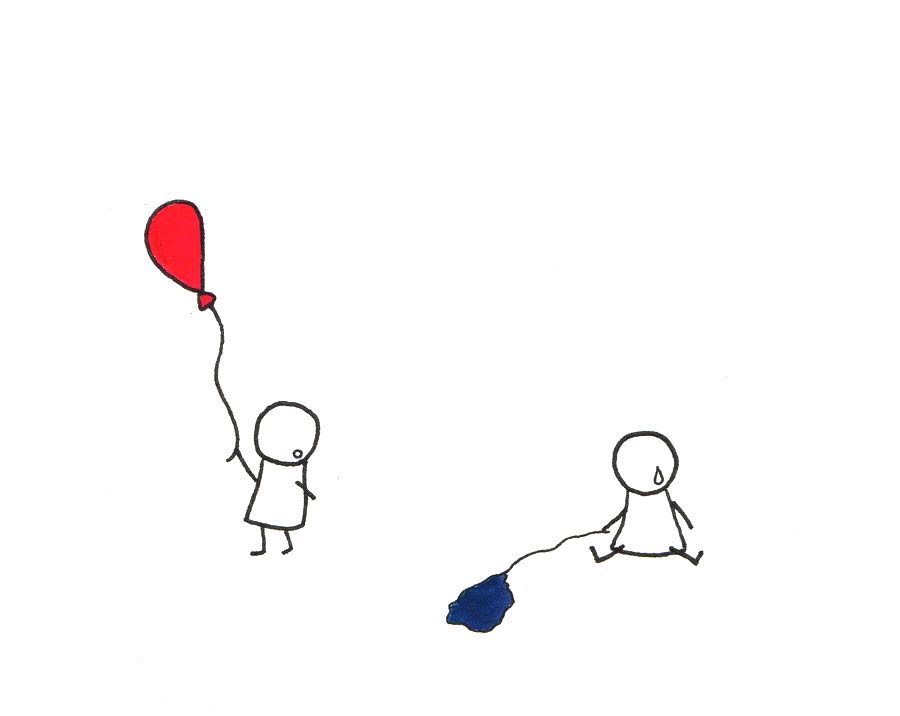

It’s a bad feeling, to know what is right and that you’re not able to do it. Or, worse, to know in a small corner of your mind that you could do it, if you absolutely had to, but to choose instead what US climate writer David Wallace-Wells calls a “creamily frictionless life”. In keeping our one car, we’re certainly avoiding bumps: we have two young kids, weirdly timed shifts, and lives that criss-cross the Harbour Bridge. Does that make our choice okay? Maybe. I often wonder what our kids will think of our decisions, down the track.

According to the same data, many New Zealanders put too much faith in tweaks that are easy to do. When 1000 of us were asked to pick the three most impactful actions from a list of 60, it was recycling, food-growing, switching to renewable energy, and buying less packaging that came out top. In fact, recycling is the 59th most helpful thing for the environment, growing your own food 23rd. (See the graphic on page 76.)

Our perception doesn’t align with reality, and at an individual level this is understandable. But it’s something else entirely to be in charge of population-level systems change—the type of jolt we urgently need—and to make things worse. Such as ushering extractive industries past legislative red tape, as per the pending Fast-track Approvals Bill. Or fumbling a much-anticipated global treaty on plastic pollution, as happened in South Korea this month.

As we go to press, news is breaking that the government is cutting humanities and social sciences from the Marsden Fund—New Zealand’s premier funding source for cutting-edge fundamental research across all disciplines, the cornerstone of transformational science for three decades. The focus is now on science linked directly to economic growth.

As we have outlined in the past month, New Zealand Geographic takes an apolitical stance, but rarely misses an opportunity to point out the consequences of policy. It doesn’t take a Marsden-level scientist to see the problem in defunding public health right now,—that’s on the hit list. Nursing, too. Māori and Indigenous studies. Urban design and environmental studies; community and health psychology. Research from the physical sciences will also be defunded if not directly connected to economic growth.

The decision prompted some of the strongest language I’ve ever heard from scientists, including those who stand to benefit from a greater share of the pot. “Dire,” they said. “An outrageous indictment.” “Horrified.” “Absolutely disgusted.”

Science, like societies and ecosystems everywhere, is interconnected. Pull out enough bricks and watch the tower fall.

Troy Baisden, co-president of the New Zealand Association of Scientists, said the association “deplores key aspects” of the decision. “Climate change is an area where we know half the challenge is social science and that humanities can be vastly important to support public understanding and communication.”

In other words, the gulf between perception and reality just got even bigger.