The great recycling delusion

At best, our recycling system is deeply inefficient. Some argue it’s also a deliberate deception—an industry ploy to stop consumers thinking too hard about buying stuff in the first place. But one small town is carving out a better way.

Chris Hipkins and Christopher Luxon didn’t agree on much of the big stuff in the first TVNZ debate ahead of the 2023 general election. The party leaders clashed on housing, crime and co-governance. They bickered on water infrastructure and youth offending, health and education.

But on the question of which actions they were personally taking to address the climate crisis, they were in perfect harmony. “As a family we embraced recycling some time ago. About a decade ago,” said Luxon. “I’m a recycler,” Hipkins concurred.

Wellington environmentalist Hannah Blumhardt and her partner, Liam Prince, were watching the debate live. Neither could contain their despair. “I looked at him. He looked at me. And we put our heads in our hands and wailed,” Blumhardt says.

Blumhardt and Prince have been full-time zero-waste advocates for almost a decade. They got rid of their rubbish bin in 2015, in part to prove it’s possible to live without one, then spent years on the road, visiting community groups, schools, and businesses to deliver presentations on how people could take steps toward doing the same. Now, Blumhardt felt like she’d been banging her head against a brick wall.

She and Prince announced that they’d stop talking about recycling and focus entirely on other ways to reduce waste. Recycling was already getting far more credit than it deserved.

[Chapter Break]

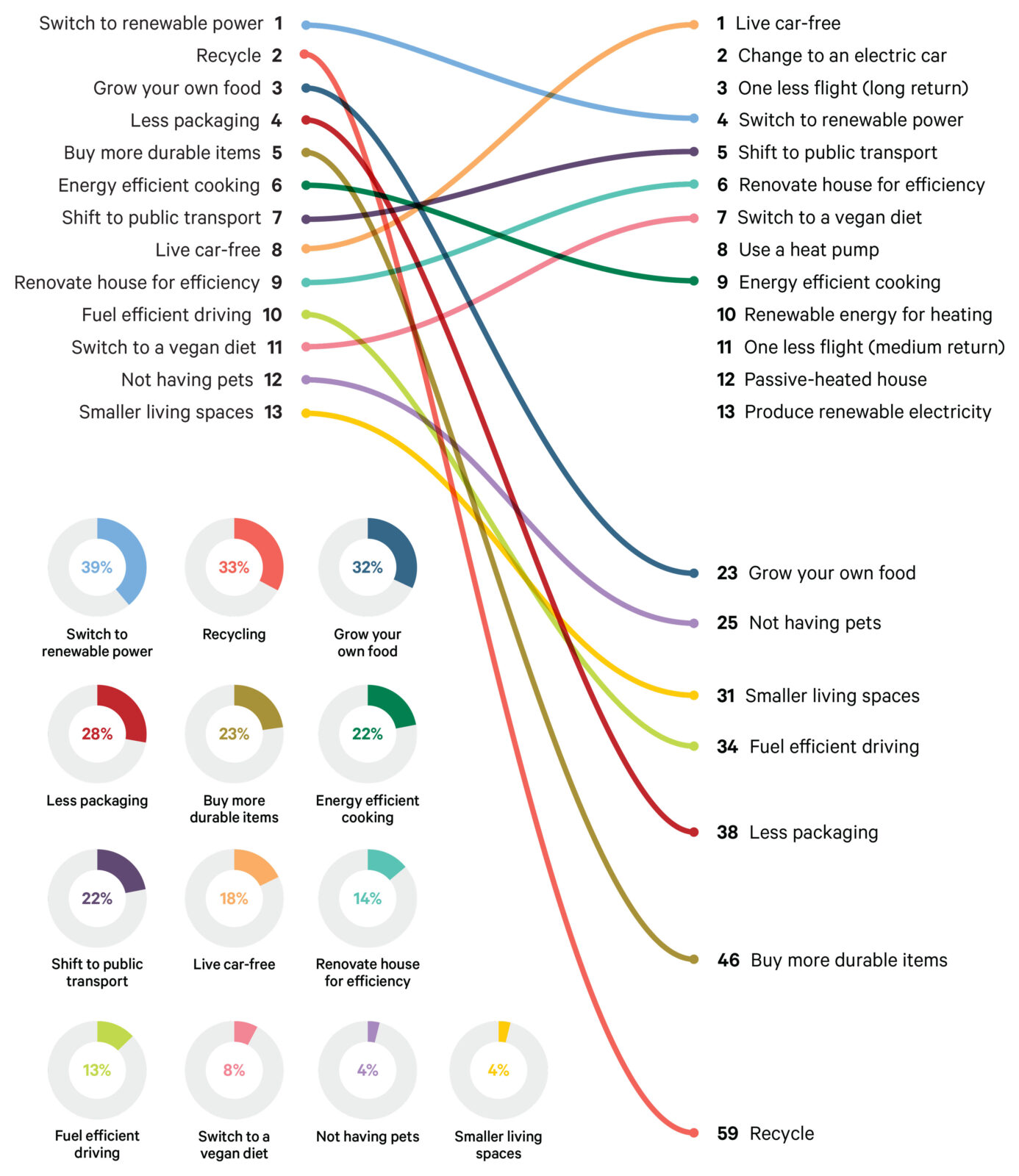

Luxon and Hipkins are far from alone in thinking recycling is the most effective way to save the planet. A recent Ipsos survey asked New Zealanders to name the top actions they could take to reduce their emissions. A third picked recycling, making it the second-most popular choice, behind switching to renewable energy. In fact, recycling is only the 59th most effective action people can take to reduce their personal emissions, according to Ipsos, well behind not having a pet (number 25) and driving more slowly (number 34).

So, recycling doesn’t help fend off the climate crisis all that much. But doesn’t it at least stop a huge amount of stuff from rotting away in landfills?

People certainly think so. Asked to reduce waste, most of us point toward recycling. Fewer than half think about the simpler option: buying less.

It would be useful to be able to hold up hard statistics here—data on what happens to all the milk bottles and baked-bean cans and muesli-bar boxes we so diligently sort into their correct bins. Frustratingly, some basic numbers are missing. We don’t actually know how much of New Zealand’s rubbish gets recycled, but it’s not a lot. A couple of groups have made guesses: the industry-backed group Waste and Recycling puts it at 15 per cent and the Ministry for the Environment gives a more optimistic 32 per cent estimate.

We do know that some of the stuff we try to recycle ends up in the dump. During a summer camping trip to an Auckland regional park, my family meticulously sorted our waste into the elaborate rubbish, recycling, and food scraps bins set up near the camp entrance. When the truck trundled in for collection on a drizzly Tuesday morning, the driver sidled out of the cab, hooked the plastic bags from the recycling and rubbish bins up to a winch, and held them aloft over the vehicle’s rear container. Their contents spewed out in a jumble, together.

Maybe that waste was re-sorted at a collection centre. But if it did go straight to the tip, it wouldn’t be an isolated incident. Following a Fair Go investigation in 2022, Auckland Council and several other local authorities admitted that they send the contents of their recycling bins from public places like city parks and town centres straight to the tip, because they’re too contaminated with other rubbish to make sorting them feasible or worthwhile. Parul Sood, who at the time was Auckland Council’s waste solutions manager, told Fair Go the bins were mainly there for “educational” reasons. The council’s policy and planning committee chair, Richard Hills, says he’s now ordered a full review of the public recycling bins to see whether there’s any point in having them.

But, Hills points out, the public bins are only in “a few parks and a few streets” and collect a small minority of the city’s waste. The recycling bins collected from kerbsides fare better, though 16 per cent of what’s inside them is contaminated, too.

Even when a piece of recycling is nice and clean and ends up in the right bin, how well it can be recycled varies. Recycling works fine for glass or aluminium. But plastic is a different story. When plastic is recycled, it degrades. Treated properly, it can manage a second or possibly third life—then it heads to landfill.

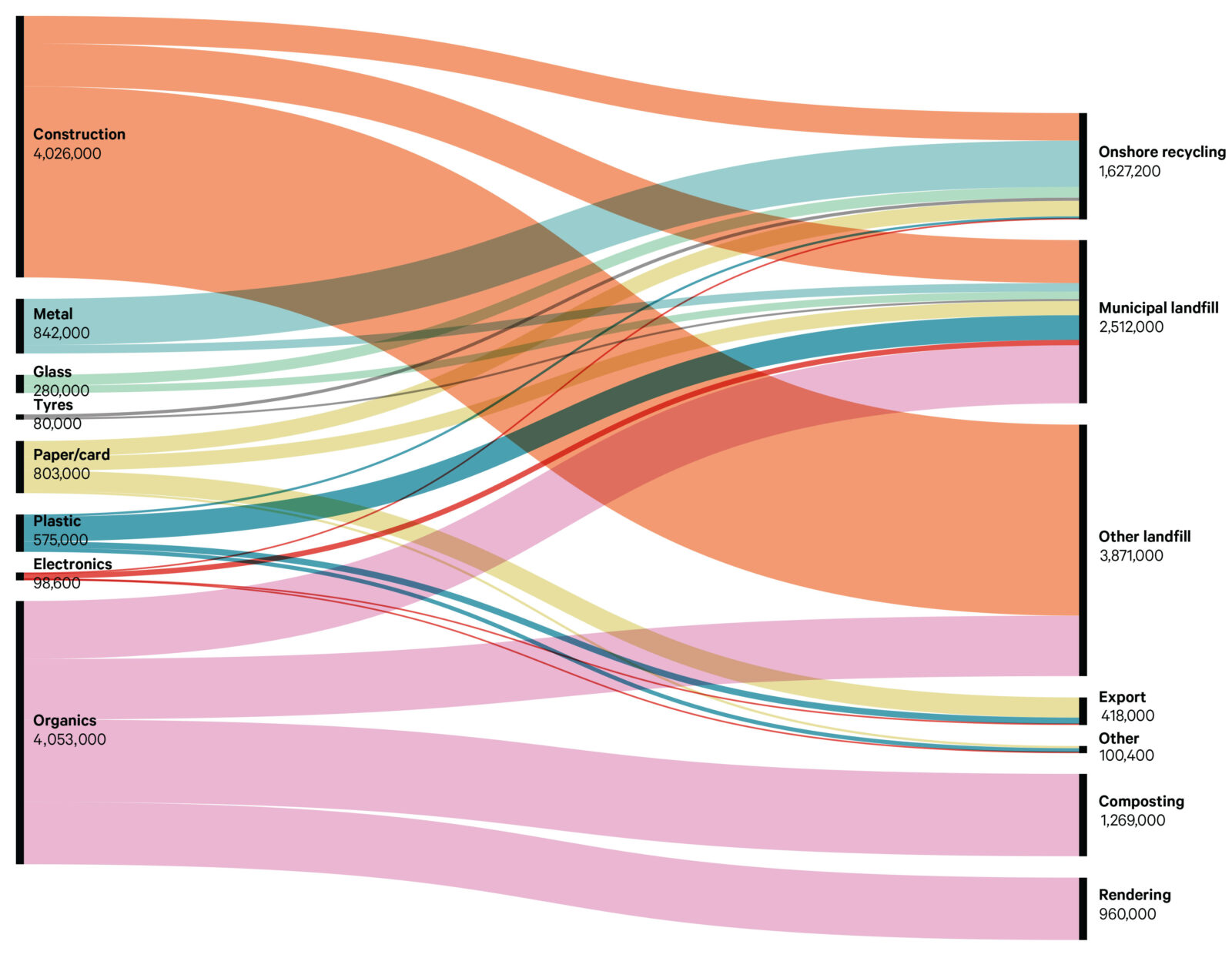

Meanwhile, we’re producing more rubbish than ever. Our collective mountain of annual landfill waste rose by more than a third between 2009 and 2018. Most of that isn’t coming from kerbside bins: about half of all New Zealand’s waste comes from construction and demolition. Business and industry account for another quarter, and farms 10 per cent. Only 12 per cent of the rubbish mountain comes from households in our towns and cities. In short, all our rinsing and sorting of juice bottles and Christmas detritus—all those last-minute dashes dragging bins down the drive in our dressing gowns—is actually only partially dealing with a percentage within a percentage of a tsunami of waste.

[Chapter Break]

Some environmentalists see deception—or at least cynical PR—in that chasm between belief and reality, particularly when it comes to plastic. Center for Climate Integrity researcher Davis Allen says plastic producers have deliberately obscured the truth about recycling in an effort to protect their social licence to keep polluting. “We have all these enormous costs associated with plastic waste,” he tells me in a Zoom call from his US office. “They’ve lied to us about the solutions. They should be responsible for addressing the issue.”

It’s a big allegation, but Allen has evidence to back it up. He’s one of the authors of a recent paper titled “The Fraud of Plastic Recycling”. The paper, which got worldwide media traction, draws on dozens of internal industry documents to claim Big Oil and large industrial plastic producers like ExxonMobil and Chevron Phillips have long known recycling isn’t a technically or economically viable solution for their waste. As early as the 1980s, the paper says, the industry was acknowledging that recycling would never truly head off the problem of plastic pollution.Executives promoted recycling anyway, because it was in their interests if people thought they could deal with plastic waste by putting it in a different-coloured bin. There had already been calls to regulate the industry or even shut it down altogether, and that was far less likely to happen if a seemingly effective solution was in place.

[sidebar-1]

Allen’s paper catalogues the sell job in detail. There were PR and advertising campaigns co-opting the language of environmentalism. Local authorities were convinced to sign up to recycling pilot programmes that were initially part-funded by the plastics industry, then stuck with the bill when the private investment ran out. “Sometimes with complicated, large issues, it’s hard to lay blame anywhere in particular,” says Allen. “With this, it’s been shocking how clear it is that the companies are the ones who have created the whole problem. They’re so—when we look in the documents—blatant about it.

“They’re so direct about the fact that it won’t work and that they’re trying to convince people it will anyway.”

There are some caveats here: Allen’s paper primarily focuses on US and European markets, and many of the documents it relies on are decades old. Plastic is only one part of the waste stream, and recycling is more viable for other materials including glass, aluminium and paper. Still, some of the paper’s overarching messages hold true for Aotearoa. The company Future Post, for example, has been celebrated and lavished with positive PR for its efforts to turn plastic waste—which it’s paid to recycle—into fence posts. In late April, a Stuff investigation found it had been dumping truckloads of plastic, including granulated plastic that had apparently already been processed, in a neighbouring landfill.

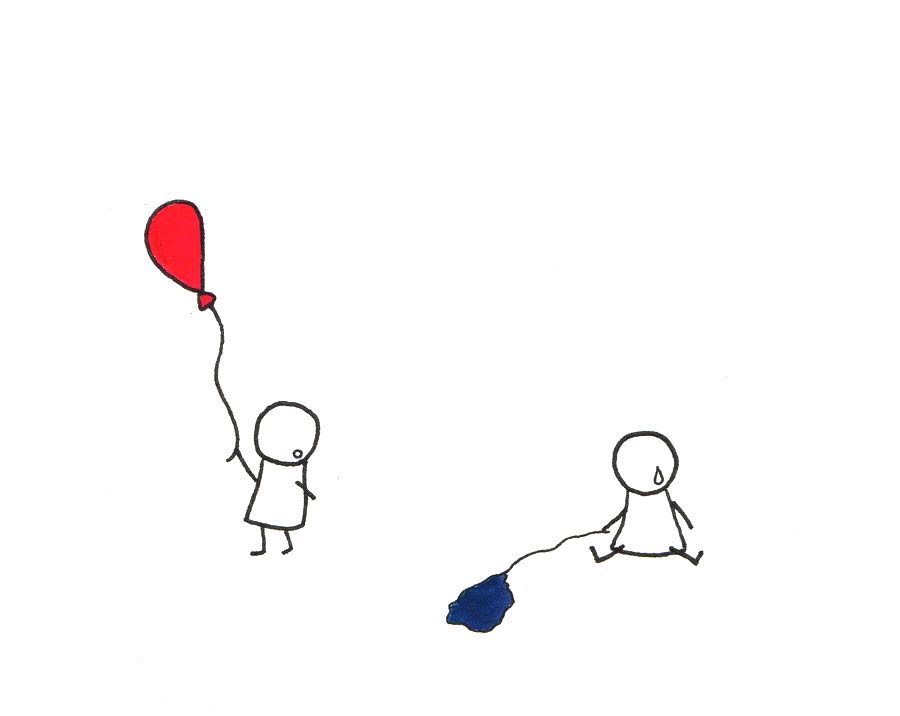

Zero Waste Network’s Sue Coutts sees recycling as more PR than panacea for products such as plastic which degrade into a lower-value material as they’re recycled. A plastic milk bottle might find a new life as a fence post, but we’ll still need to extract more fossil fuels out of the ground to replace the original product, provided people keep drinking milk. “To the extent that recycling is a closed loop and makes a product that’s like-for-like, it makes some sense,” says Coutts. “But that should be the absolute bottom line. If you’re starting to slide into downcycling, then really it’s more of a greenwash strategy.”

Likewise, Greenpeace plastics pollution campaigner Juressa Lee (Te Rarawa, Ngāpuhi, Rarotonga) says any solution that doesn’t stop new waste coming into the system is essentially a con. “We’ve been had for a long time. Recycling doesn’t turn off the tap,” Lee says. “If we are serious about the climate, if we are serious about pollution, then the only way is to turn it off at the tap.”

There’s concern recycling may actually be turning the tap up full bore. Warren Fitzgerald, a PhD researcher at Te Herenga Waka–Victoria University of Wellington, is looking at whether recycling is taking the edge off our guilt about buying stuff which will end up in the bin. His work is qualitative. It’s based on interviews and observation rather than hard data. But it’s worth noting that in one of the simulations he designed, increasing recycling rates actually made overall environmental outcomes worse.

“Effectively, the act of recycling makes us feel good about it, and creates a justification for us to go out and consume more,” he says.

Zero-waste advocates say these issues are compounded by the fact that government and council investment is heavily weighted toward recycling at the expense of other waste minimisation tools. They bemoan not only the inadequacy of the recycling system for dealing with waste, but its unfairness to taxpayers and ratepayers, who end up being lumped with the bill for cleaning up the junk that polluting industries generate. Lee calls it a prime example of “privatising the profit and socialising the cost”. Blumhardt is exasperated at polluters benefiting from the PR cover recycling provides and not paying for the service. “They’re just laughing all the way to the bank,” she says. “And on top of that, people think it’s a good thing, and the mental labour it takes to recycle for the average household, well that’s them spent in terms of their environmental action, and in terms of the waste budget for council, it’s gone.”

[Chapter Break]

Still, at a basic level, recycling does some good. It’s better than throwing stuff in the bin. Blumhardt, for instance, recycles.

“I find it quite annoying when I see people go ‘recycling is a crock’,” says Jonathon Hannon, coordinator of the Zero Waste Academy at Massey University. “Because, fundamentally, recycling is part of what we need to do.”

On that, at least, he and Plastics NZ chief executive Rachel Barker are aligned. Barker, who represents the interests of local plastic producers, has been frustrated by a string of recent pieces in BusinessDesk and on RNZ calling recycling a “fraud”. “Recycling is not the only tool in the bucket,” she says. “It’s not a magic bullet. Absolutely there’s a lot more that needs to happen. But it is still a critical tool, because if you don’t have the recycling bit of the puzzle, you actually can’t really make materials go circular and stay in use.”

Local councils also resist the suggestion that they should cut back on, or even abandon, recycling. Hills, the councillor, says Auckland Council has a responsibility to dispose of the things households are throwing out, and right now, recycling is the most environmentally friendly option on the table. “In a perfect world we would love to tell Coca-Cola or other big companies to stop using plastic, but we don’t have those powers,” he says. “So we either have the cost to landfill, which is expensive, or the cost of recycling, which is expensive. But we have to deal with the waste.”

Councils can’t tell Coca-Cola what to do. But thanks to a hefty piece of legislation passed by Labour in 2008, the government has more sway. The Waste Minimisation Act sets out an expansive set of powers for the government and standards for territorial authorities. But successive administrations have failed to use it to really crack down on waste.

Now, the government is looking at phasing out single-use and hard-to-recycle plastics. It has raised roughly $200 million through a levy enabled by the Act, much of which it has reinvested in recycling technology. But environmentalists want regulation to go faster, further, and harder. Lee says we should build on the 2019 plastic-bag ban and prohibit the use of single-use plastics as soon as possible.

Both Blumhardt and Hannon want to see landfill levies hiked from the current anaemic rates of between $10 and $60 per tonne to align with countries like Australia, which charges up to $175, and the UK, which charges $220. (A recent Ministry for the Environment report recommended $140.) The biggest issue Blumhardt and Hannon see with kerbside recycling is how it tamps down the electoral appetite for these sorts of interventions—the ones that actually work at scale—to focus on something that makes a relatively small difference to a minority of waste.

We’re taught the three Rs in primary school: reduce, reuse, recycle. Those are listed in order of importance. To Blumhardt, taking waste seriously would mean flipping how we allocate our funding and time and sending 80 per cent of our budget to the reduction and reuse of waste. “And if we only have five hours a week and five per cent of the budget to be managing kerbside recycling, then it will be what it will be.”

Sue Coutts from the Zero Waste Network is on a similar wavelength. “We’re sitting on the ground going, ‘Oh, all this plastic is coming over the cliff towards us. What’s the best thing to do? Do we put it in the landfill? Or shall we burn it?’ That’s the wrong place to be asking the question. We really need to look further up and say, ‘How do we stop all this plastic coming off the cliff in the first place?’”

Industry figures, perhaps predictably, aren’t so sure about stopping what’s coming over the cliff. Barker points out that many of our industries and public services rely heavily on plastics.

Go into any supermarket and you’ll be surrounded by food wrapped in plastic—it keeps bread fresh, biscuits crispy, and stops chicken juice dripping all over the rest of your shopping. At home, you’ll stash your haul in a fridge, key components of which are plastic, maybe flick on the heat pump—almost entirely plastic—and pick up the TV remote. Plastic.

“If we took all of our plastics and just got rid of them overnight, our medical system doesn’t exist, our transport system doesn’t exist,” says Barker. “We don’t have renewable energy technologies any more. We don’t have solar panels, we don’t have wind farms. We don’t have the technology we use today.”

She sees our waste management system less as an overflowing bathtub and more like Wellington’s water network. “We have a problem with plastic leaking into the environment, just like leaks in a water system. That is obviously an issue. But if you turn off the tap in a municipal drinking-water system, people don’t have any water to drink. So you’re actually impacting their quality of life.”

Banning a new tranche of plastic may also not help the environment as much as we hope. David Howie, who’s in charge of circular services for landfill operator and rubbish collection agency Waste Management, warns about unintended side effects. Plastic could end up being replaced by other materials that have their own issues, he says. “A plastic bottle weighs a few grams, a one-litre glass bottle obviously weighs considerably more. Now if you multiply that out by the number of truckloads you distribute around supermarkets, shops, liquor stores, wherever, suddenly you say, ‘Wait, what has that done to my transport emissions?’”

But most people agree producers should take more responsibility for the waste they create. Barker and Howie can get behind product stewardship schemes, where companies are given responsibility for creating a circular economy for their goods, rather than the current linear one where the clean-up is dumped on councils. The wheels have just started to turn on one such scheme, which imposes a levy on tyre importers. Those importers pass the cost onto consumers, then give them a refund when they take worn-out tyres into collection centres for recycling.

Massey’s Hannon says product stewardship can be an “incredibly powerful tool”—when it’s designed by experts rather than industry groups. But the Labour government ditched the most impactful product stewardship initiative proposed in decades. It had planned an “old-school” container return scheme which would have given people a small refund for returning used cans and bottles. The plan went into the policy bonfire when Hipkins replaced Jacinda Ardern as prime minister, and the current government doesn’t look likely to revive the idea.

For the foreseeable future, at least, it looks like improvements to our waste systems may have to start local. Thankfully, one town on the west coast of the North Island is providing a template.

[Chapter Break]

Rick Thorpe is at the offices of Xtreme Zero Waste in Whāingaroa/Raglan, talking through the moment the town decided to make a 180-degree turn on its approach to rubbish. It was 1998, and the local landfill was reaching the end of its life. For decades, when residents wanted to get rid of something, they’d been taking it to the tip and dumping it on the stinking heap, free of charge.

Thorpe saw a different future. With a small cohort of locals, he sold the town on taking over the dump from Waikato District Council. Within 18 months they were diverting 70 per cent of Whāingaroa’s rubbish away from landfill—a figure orders of magnitude higher than any of our major centres. That number now sits at between 75 and 80 per cent.

Much of that is thanks to the centre’s meticulous hand-sorting of its recycling. But Thorpe doesn’t see the recycling system as the first or best destination for the town’s rubbish, which he studiously refers to as “resources”. A secondhand store sits right next to the recycling centre, selling stuff people have thrown out: $5 for a grey travel bag, $3 for sunglasses, $1 for a mostly intact copy of Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian. Several of the non-profit’s 40-odd staff run education workshops for visitors and schoolchildren on how to reduce their waste: buy sustainable products, reuse what they can. “We now have a generation of people living here in Whāingaroa who don’t know about landfills,” says Thorpe. “They have only had a zero-waste programme. So they have high literacy around waste issues, and they are changing the way in which they consume and purchase things.”

That’s fostered a distinct culture, not only in the town’s households but its business community. Over at The Workshop Brewing Company, Bruno David is speaking with almost manic energy about his efforts to reduce waste. The brewery’s co-founder has an exercise book open on the taproom’s bar. It’s filled with pages of dense notes on why glass bottles are more eco-friendly than cans for his operation. Nearly all of his equipment is scavenged, reused, or jerry-rigged out of rubbish. A table is made from a tawa tree that came down on the property. The brewery kettle is an ex-dairy vat. Its hot liquor tank was found in the middle of a farm. He binds his six-packs up with special cable ties, which the team at Xtreme Zero Waste sort and return to him for reuse.

But David is still frustrated. At the moment, nearly all the country’s beer bottles are manufactured at the Visy Glass facility in Auckland, which doesn’t make reusable containers. He can’t afford to set up his own reuse system, and he’s not really incentivised under our single-use consumer culture to act sustainably.

“Why are we not looking at keeping the integrity of something that’s already gone through the energy process, and placing a proper value on this?” he says, as he taps on a bottle. “We’ve made energy too cheap. It’s so cheap that we’ll smash this up and recycle it into a bottle again. I mean, that’s crazy. Like, it’s absolutely ludicrous.”

Both the passion and frustration seem contagious. Ten minutes up the road at Dreamview Creamery, Jess Hill gestures to a cluster of metal bins filled with bottle lids. “It just annoys me,” she says. “It’s like, we reuse everything else perfectly and then there’s these.” Hill is perhaps a little too self-critical. Dreamview runs a milk delivery service for 3000 people. When subscribers are done with a bottle, it gets collected, washed and reused at the creamery headquarters on the hills overlooking Raglan and the Whāingaroa Harbour. In six years, Hill’s operation has stopped 2,214,826 plastic bottles being sent to landfill. Those lids are the only things that get thrown out.

It’s tempting to think a successful waste management system has to look like Xtreme Zero Waste. That can be the case. Thorpe is going around the country proselytising. He’s helping to set up a zero-waste facility at Waiuku, and working on recycling-based product stewardship schemes with Fonterra, IP Plastics in Papakura and the plumbing and civil infrastructure company Marley. But Hill points out that often, good waste management looks like an absence. She regularly travels down to The Shack, a cafe in the Raglan town centre. Its recycling bin used to be overflowing with plastic milk bottles, until it got Dreamview to supply its milk. Now its bottles get picked up and delivered back for reuse.

If you look out the back of the cafe now, in the bare concrete courtyard where it stores its rubbish, you’ll find a stack of cardboard and some cans. But the bin for paper and glass is mostly empty. The cafe is recycling almost nothing, and it’s never been more clean and green.