Up time

There are many ways to escape. Every morning, early, I sneak out to the kitchen, open the doors to the garden, and listen to the blackbirds and tūī chortle themselves awake. For half an hour, I am somewhere else.

The American poet Mary Oliver was a kindred spirit. She wrote over and over again of the dawn, what she called “the opening of the door of the day”. “This is to say nothing against afternoons, evenings or even midnight,” she wrote in her 2016 book, Upstream. “Each has its portion of the spectacular. But dawn—dawn is a gift.”

(After Oliver’s death, in 2019, Kennedy Warne wrote a piece entirely about her—perhaps the only poet to get such a run in this magazine. See Issue 156.)

Oliver was deeply religious and I am not, but in that liminal beat before the light I find reverence, at least; the crickets and the cicadas are all singing at once; it seems that the big willow in our garden is bowing; it feels like the moment before you breathe out.

After a little while, about the time it takes to drink a cup of Earl Grey, the sun jumps the back fence and I pivot to lunchboxes, sunscreen, the doing of the day. I am always, already, looking forward to the next morning.

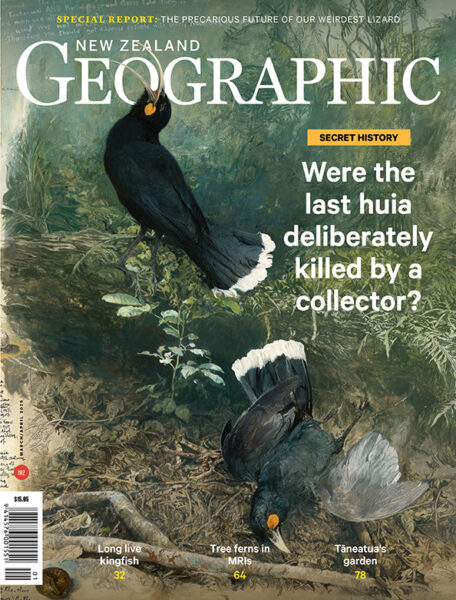

When I read Anna Yeoman’s story about harlequin geckos (page 94) what threw me most, of all their strange habits, was that unlike most lizards they tie their activities to weather, not the rising or setting of the sun. They’ll just as happily hunt at midnight as noon, so long as it’s warm enough.

When my boy was tiny he woke every day at 5.30am on the button. Our house was uninsulated then, with cold wooden floors. So after a quick breakfast we’d just get dressed and leave. The ruru in the gully over the road would be hooting and we’d hoot back as I fiddled with the car seat. We’d be first in the doors when Pak ‘nSave opened at 7am. The bakery guys would be singing; they’d give my boy a bread roll to chew on and a paper bag to wear as a hat. We would take 40 minutes to buy frozen peas and yoghurt. We were so unbelievably tired. We had everything we could possibly want.

Reporting the kingfish feature on page 32, I decided to trek out to Cornwallis wharf at 5am on a public holiday, to catch a fishy tide and the people trying their luck. My early-bird boy, now 10, didn’t have to come with me but he desperately wanted to, and so we drove through the dark with a podcast and a Thermos of Milo.

At the beach he curled up on the grass with a book while I wandered the hushed, busy wharf.

The first people I talked with, while the gulls were still sharp black shapes in the sky, were Cecile and Alan from the North Shore. Alan was fishing but Cecile was just looking at the sea. The couple work all week but every weekend they’re here at dawn, Cecile told me. The rising sun was pink on her face. She pointed out their favourite spot on the rocks. Alan, she said, learned to fish in the Philippines and had been praying for a kingfish. Then she leaned closer.

“We don’t really think that we can get any,” she said. “We’re only just here to feel free.”