What is the hullabaloo about the Hauraki Gulf, and what on Earth is ring-net fishing?

Well, I’m glad you asked. Turns out the answer to both of these questions is complicated.

Last weekend the Minister of Conservation announced that some of the proposed high protection areas for the Hauraki Gulf—perhaps two—would allow a commercial method called “ring-net fishing”, inside the reserves.

Conservation organisations and institutions expressed shock and outrage. It boiled over into the daily media, but there were more questions than answers. Chiefly, why? Secondly, what on Earth is ring-net fishing?

While we wait on the actual wording of the draft amendments, let’s review what we know.

Ring-netting, as far as anyone can tell, is a more politically palatable badge for grandpa’s gill net. Floats at the top, weights on the bottom. If you leave it unattended it’s called a set net, an indiscriminate killer of anything that swims its way—eagle rays, snapper, kingfish, mullet, kahawai, sharks, dolphins… whatever, the net doesn’t have preferences.

But use the same net from a small boat, circle a school of your preferred species—say mullet, kahawai—then lift it immediately, the by-catch is probably quite limited, the bottom contact minimal. Arguably this is a low-impact form of fishing that we should be encouraging. So what’s the big deal?

The big deal is that the only function of marine protection is to prohibit extraction. There’s nothing magical. It works by allowing fish within the protected area to return to natural abundances—research suggests five to seven times greater than in unprotected waters within six or seven years—and to allow the dividends (in the form of larvae, eggs and fish) to spill out into surrounding areas in a well understood phenomena called the halo effect. Congratulations, you have built a fish pump.

Does marine protection work when you extract fish from the protected area? No. Do you get a halo effect? Of course not.

Fishing out a spawning stock strategically protected to benefit the wider ecosystem is like running down an investment that provides interest as cashflow. It doesn’t make sense.

But is it better than nothing? Yes it’s slightly better than nothing. This is because the type of fish typically targetted by gill net fishers are schooling fish like kahawai and mullet. They have less direct contribution to the shape of the ecosystem than, say, snapper and crayfish which control kina and promote kelpy, diverse habitat. It’s likely you will still see some ecosystem recovery, albeit with a low abundance of schooling fish.

How can we be sure? Scientists have studied the before-and-after effects of marine protection for half a century. We know that no-take protection works, and we also know that protection that allows for catch can critically compromise the efficacy of a protected area. The Mimiwhangata Marine Reserve is a good example. Established in 1984 the area prohibited commercial take but allowed recreational take, limited to rod-and-line only. However the reserve status attracted increased fishing pressure and resulted in even lower fish abundances than in adjacent waters. It was worse than had the reserve not existed at all, and fishing was prohibited by a review in 2013.

What the government’s amendment in the Gulf Bill achieves, however, is a transfer of rights from public ownership to private—into the hands of “five or six” operators. The economic gains are likely insignificant and the public-good of ‘feeding South Auckland’ is probably misrepresented, if not offensive. This doesn’t make sense either.

Minister of Conservation Tama Potaka has justified the amendment by saying he is merely attempting to seek “balance” in the Bill. Yet the ‘balance’ has already been found. After some 15 years of negotiation, commercial and recreational fishers, iwi and other stakeholders arrived at a very difficult compromise: 6 per cent of the Hauraki Gulf would be set aside to recover, and 94 per cent (more than a million square kilometres) would remain available for fishing. Why is it necessary to seek more balance within the 6 per cent? We don’t know.

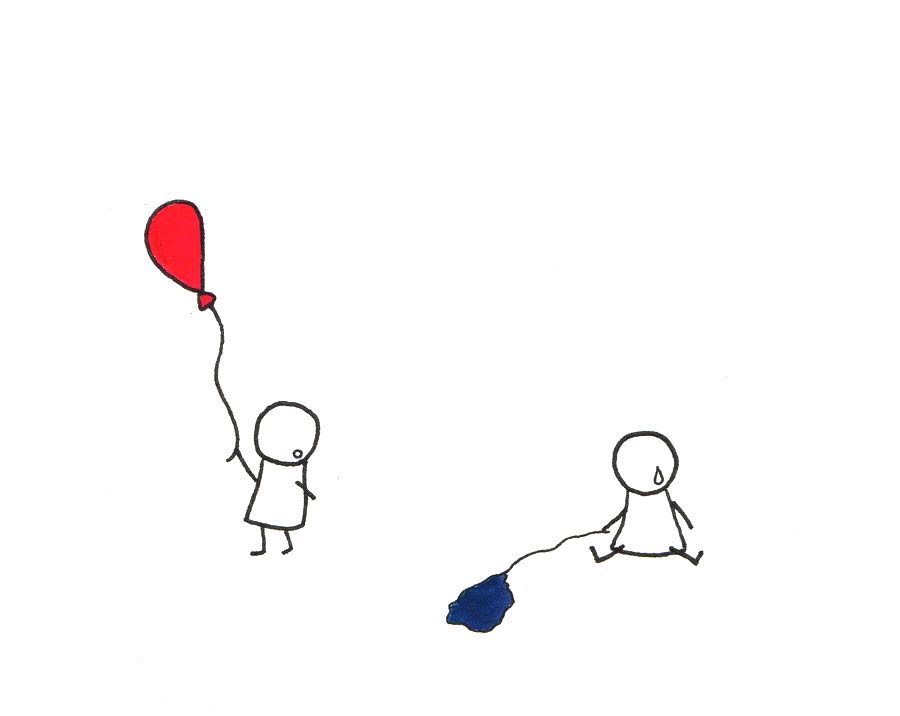

Across the week, environmental advocates and the wider public have fallen into two camps. One takes a hard line: If we allow commercial fishing inside protected areas it will cripple the reserves, defeat the central purpose of protection and perhaps worse, create a precedent that will mean every subsequent protection is a compromising negotiation over rights rather than a discussion of ecosystem values and public benefit.

The other camp, having battled for these protections for 15 years, views this as an awful compromise, but one they may be willing to take in order to get the Bill approved and the benefits realised in a marine area where total ecosystem collapse is a clear and present danger.

Is it a difficult concession or a dangerous precedent? Yet again, everybody wants an abundant and thriving environment, but agreeing on the path to get there depends upon your frame of reference. If you have a view, don’t just rage on social media, tell your MP.