Flying visit

MOTAT is striking a balance between the past and the present with a new exhibition called Hautū Aunoa Autopilot.

MOTAT is striking a balance between the past and the present with a new exhibition called Hautū Aunoa Autopilot.

OE McLeod with RM Briggs, CE Conway and O Ishizuka Geoscience Society of New Zealand, $75

Whales sing more when there’s oodles of food around, researchers have discovered. A team based at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute analysed whalesong picked up on hydrophones in the nutrient-rich seas off California. The first tapes were from 2015, when a marine heatwave was decimating the food web. That year, humpback whales sang on only about one-third of days, but as krill rebounded, followed by another humpback favourite, anchovies, singing picked up accordingly. After six years, the humpbacks were singing on 76 per cent of days. Blue whales and fin whales in the area followed similar patterns, singing more when the sea was brimming with krill. The researchers peeled away other possible variables, but the relationship between food and music stuck. As eating enough to fuel those massive bodies gets easier, the researchers suggest, there’s simply more time for singing.

Remember the sky on New Year’s Day of 2020? Across the South Island the air was thick and hazy, the sky an eerie yellow. Satellite images showed a brown cloud of smoke from massive Australian bushfires stretching all the way across the Tasman. When it reached the North Island, clouds over Auckland turned an apocalyptic orange. About the same time, caramel-coloured dust appeared on Fox and Franz Josef Glaciers and blanketed the snow cap on the Southern Alps. This was caused by the bushfires, too, the media reported. Or was it? Photography showed the dust coating the alps weeks before the late-December bushfires. New Zealand researchers analysed dust samples and found it actually came from the Australian desert, not the fires, and was carried across the sea on extraordinarily high winds. This phenomenon is rare, but not unprecedented: desert dust has coated the alps nine times since 1902. It’s not just an aesthetic change. Dust absorbs more sunlight than ice because it’s darker in colour, so it causes snow and glaciers to melt more quickly.

The sable shearwaters of Lord Howe Island, between Australia and New Zealand in the Tasman Sea, are among the most plastic-contaminated seabirds in the world. Unsuspecting parents feed their chicks indigestible bits of plastic, mistaken for squid or fish. “It’s upsetting to see just how much plastic they’ve got, just as they’re starting life,” says Alix de Jersey from the University of Tasmania. In a study she led, one chick had consumed 403 fragments (pictured here) together weighing about the same as a slice of white bread. Some malnourished birds die. But researchers wondered whether even seemingly healthy chicks could be burdened with hidden health problems. The team ran blood tests on chicks that appeared in good nick, both with and without plastic in their stomach, looking for 745 different marker proteins. “If you feel like something is wrong, you go down to the GP for a blood test,” says de Jersey. “This is similar: a tool to see what might be going wrong.” A lot was wrong, it turned out. Stomach proteins were leaking into the bloodstream—sharp plastic can dig holes in the stomach wall, and cause a build-up of scar tissue dubbed “plasticosis”. The filtering organs—liver and kidneys—were failing, perhaps due to microplastics. And most surprising, signals usually associated with brain diseases such as dementia cropped up. This could inhibit the birds’ song-recognition ability and breeding success, de Jersey says, and future research will watch for manifestations of this cognitive decline in the colony. Sable shearwaters breed in New Zealand, too, foraging in plastic-loaded waters alongside our many other seabirds, such as Cook’s petrels and mottled petrels.

Solutions to some of our most pressing problems have been waving at us from under the sea, all along.

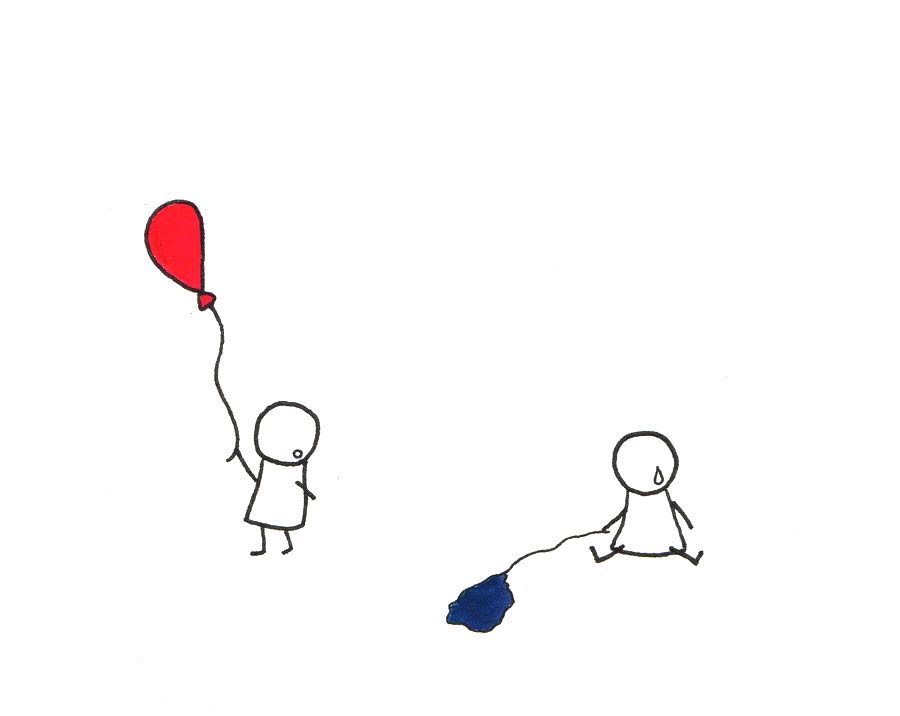

My inbox is a world of hurt. Eels dead on beaches. Seabirds starving. Ice, melting faster than we thought. There are microplastics in our brains, my emails advise me, and in the breath of dolphins. This morning, an ordinary, terrifying line in a press release: “The climate crisis is a threat to civilisation.” No time to think about it, not really. Back to trying to write a coverline that’s cool and intriguing but also true. Now the phone’s ringing; a writer with field-work plans gone awry… I’ve found that it helps to have a sense of mission. To understand your “why”. For me, it’s the hope that documenting our world might help save it; even on the most stressful days, this idea feels like a flying-fox zipping us over the trees. I see a similar, singular focus in the seaweed scientists and entrepreneurs Kate Evans and Richard Robinson meet in their cover story on page 78. “For me personally, seaweed provides a sense of hope,” says Coromandel CEO Lucas Evans, who, because of that hope, slid down a rabbit hole of seaweed science eight years ago and is now permanently ensconced. I think about the moment the tight-knit team of Plant & Food Research scientists confirmed that their seaweed spray can help defend some of our most important crops from diseases. I even find myself identifying with the tech-bro of the piece, entrepreneur Steve Meller, who could have settled for a “nice little 20- or 30-million-dollar business” selling methane-busting seaweed supplements to farmers, but is aiming higher—as in, he wants to help save the world. Move fast and fix things, is the vibe. Maybe miracles can happen, if we work hard enough—and don’t get distracted. I got a great gust of that energy, too, from Coromandel conservationist Sara Smerdon. She talks fast and hard; replies to emails within moments. We’ve been hammering out the finer points of how pigs and other pests go about scoffing native frogs in the ecologically rich forest to which Smerdon is devoted (see Naomi Arnold and Rob Suisted’s story on page 36). Every call, I had a notepad to hand just in case, and it ended up covered in shorthand. Smerdon talked about the incredible critters that live in this spot. How she felt when she found pig sign all through rooted-up frog habitat—and then saw the same devastation again, and again. How she and others pushed for the evidence that might prompt action. And how hard it is, always but especially now, to get money to fight for our forests. “These frogs have so little protection anyway,” she told me. “This is why we do what we do.” Last summer, we asked readers for feedback on this magazine. We’ve printed out all the responses and sometimes, when the to-do list gets on top of me, I pull out the stack and read through it all again. “Continue to explain the why,” you told us. Someone else: “It is great to see passion in the writing and photography.” Others: “I want to hear the awesome stories of people doing good and interesting work in these dark times.” “Be brave. Stand up for science and scientists.” “Follow your gut always.” One person told us they wept over our feature about red-billed seagulls (Issue 187). “However, I accept that we need to know about these things and I don’t want you to stop covering them.” Often, the stories we tell in New Zealand Geographic are bleak. But in every story, we strive to show you that there are people like Sara and Lucas and Steve—clever, ambitious, stubborn people—who are getting stuck in because they care just as much as you do. We hope it might help you hold on to your why.

Una Cruickshank, Te Herenga Waka University Press, $35

One hundred years ago, we thought IQ tests could predict the future.

The tragic trajectory of deep sea bottom trawling just got a lot weirder.

The other morning I set a deeply unimpressive personal record. The drive to work, which usually takes 45 minutes, stretched out to an interminable 77. I sat at one intersection for more than half an hour, listening to my emails ping and wondering how I fell into this trap. So, I suspect, did everyone around me. Going car-free is the single most powerful thing a person can do to mitigate climate change, according to data published by global research company Ipsos for Earth Day 2024. That, for my family, feels impossible. Likewise, we can’t afford to switch to an electric vehicle—the second-most powerful lever on the list. (The third, though, is a cinch. Ditch one long-haul flight? Done. I hate flying.) It’s a bad feeling, to know what is right and that you’re not able to do it. Or, worse, to know in a small corner of your mind that you could do it, if you absolutely had to, but to choose instead what US climate writer David Wallace-Wells calls a “creamily frictionless life”. In keeping our one car, we’re certainly avoiding bumps: we have two young kids, weirdly timed shifts, and lives that criss-cross the Harbour Bridge. Does that make our choice okay? Maybe. I often wonder what our kids will think of our decisions, down the track. According to the same data, many New Zealanders put too much faith in tweaks that are easy to do. When 1000 of us were asked to pick the three most impactful actions from a list of 60, it was recycling, food-growing, switching to renewable energy, and buying less packaging that came out top. In fact, recycling is the 59th most helpful thing for the environment, growing your own food 23rd. (See the graphic on page 76.) Our perception doesn’t align with reality, and at an individual level this is understandable. But it’s something else entirely to be in charge of population-level systems change—the type of jolt we urgently need—and to make things worse. Such as ushering extractive industries past legislative red tape, as per the pending Fast-track Approvals Bill. Or fumbling a much-anticipated global treaty on plastic pollution, as happened in South Korea this month. As we go to press, news is breaking that the government is cutting humanities and social sciences from the Marsden Fund—New Zealand’s premier funding source for cutting-edge fundamental research across all disciplines, the cornerstone of transformational science for three decades. The focus is now on science linked directly to economic growth. As we have outlined in the past month, New Zealand Geographic takes an apolitical stance, but rarely misses an opportunity to point out the consequences of policy. It doesn’t take a Marsden-level scientist to see the problem in defunding public health right now,—that’s on the hit list. Nursing, too. Māori and Indigenous studies. Urban design and environmental studies; community and health psychology. Research from the physical sciences will also be defunded if not directly connected to economic growth. The decision prompted some of the strongest language I’ve ever heard from scientists, including those who stand to benefit from a greater share of the pot. “Dire,” they said. “An outrageous indictment.” “Horrified.” “Absolutely disgusted.” Science, like societies and ecosystems everywhere, is interconnected. Pull out enough bricks and watch the tower fall. Troy Baisden, co-president of the New Zealand Association of Scientists, said the association “deplores key aspects” of the decision. “Climate change is an area where we know half the challenge is social science and that humanities can be vastly important to support public understanding and communication.” In other words, the gulf between perception and reality just got even bigger.

Our summers are getting hotter, but electric fans are not always the answer—even if they make you feel cooler. Electric fans work by blowing cooler air across our skin and enhancing the evaporation of our sweat. Cheap and convenient, they often sell out in heatwaves. But on really hot days, a fan can flip from saviour to sauna—more convection oven than a breath of fresh air. So where is that threshold? Public health bodies have advised that older people—who sweat less, and are more vulnerable to heat—shouldn’t rely on fans when it’s hotter than 35 degrees Celsius. Modelling by one group of scientists suggests the limit is 33 degrees, while another model spat out 38 degrees—a pretty significant divergence. Fergus O’Connor, an Australian environmental physiologist at Queensland’s Griffith University, and his colleagues decided to test this question in the lab. They convinced 18 people aged between 65 and 85 to swelter in a 36-degree room for eight hours under three conditions—no fan, a fan on low, and a fan on high. The fan was placed a metre away, blowing directly on their skin (too ruffly to read a newspaper or magazine, but the volunteers were allowed Netflix and e-readers). During all of the tests, the subjects’ body temperatures spiked to a mean of 38.3 degrees. “The fan had no benefit whatsoever,” says O’Connor—though it didn’t make things worse, either. Under the highest setting, blowing at four metres per second, subjects reported feeling slightly cooler, but their body heated up regardless. O’Connor’s team haven’t yet tested the fans under other temperatures. But he advises that when the mercury rises past 33 degrees or so, you’re better to find an air-conditioned public space—perhaps your local library—rather than rely on a fan.

Small marine creatures can hitch lifts on floating objects all the way to Antarctica, a new study suggests—and as climate change makes the icy continent more hospitable to colonisers, that’s a problem. The study, published in Global Change Biology, involved researchers from New Zealand, Australia and the US and was led by Hannah Dawson, now at the University of Tasmania. Scientists have long known that rafts of bull kelp sometimes wash ashore in Antarctica, Dawson says, but the only way to trace the origin of each clump is genetic testing. “To get the big picture, it’s not very practical to walk around the Antarctic coastline trying to find all the washed-up things to test them.” Instead, using the computer equivalent of dropping a stick in a river to see where it ends up, the team released millions of virtual particles into 19 years’ worth of ocean currents data. The results show floaters such as bull kelp, plastics and driftwood can arrive from much further away, and more often, than previously thought. These rafts could carry all sorts of species, including shellfish and crustaceans, snails, sponges, starfish and urchins. Most rafts take around a year to cruise to the continent—arriving not only from sub-Antarctic islands, but also from all the major Southern Hemisphere land areas, including Australia, South Africa, and South America. New Zealand is a major contributor, with floaters riding the currents that hustle between the east coast of the South Island and the west coast of Antarctica. “This kind of rafting is a natural process that’s probably been happening for a long time,” says Dawson. “But the concern is that warmer water and less sea ice reduce the barriers to arrival, and open the door for non-native species on the rafts to colonise those waters.” In the graphic, colours indicate where floaters washed up. Most-hit was the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, a region with relatively warm water and often ice-free conditions—a prime spot for newcomers to set up camp.

If our memories make us who we are, what’s it like to have a different type of memory entirely? What can animals remember? Do goldfish have a memory longer than three seconds? And can plants remember anything at all?

Well, I’m glad you asked. Turns out the answer to both of these questions is complicated.

New Year’s Day, 1967. North of Auckland, marine biologist Bill Ballantine decides he’ll kick off the year by taking the temperature of the sea. This is how one of the longest ocean-temperature records in the Southern Hemisphere begins. In 2022, the record chalks up its hottest year: the Hauraki Gulf is in heatwave mode 86 per cent of the time. It’s the same story for the rest of the country. The oceans surrounding New Zealand reached their highest-recorded temperatures either in 2022 or 2023, according to data released last month by Stats NZ. Our coastal waters warmed between 0.74 and 1.35°C in the past four decades. What does this mean for sea life? Fifty million Fiordland sponges were wiped out by an intense heatwave in 2022, New Zealand scientists report in Global Change Biology—the largest such dieoff ever recorded worldwide. Now, Stats NZ is keeping an eye on phytoplankton, the invisible plants which sustain marine food chains. Their numbers have been decreasing in New Zealand waters since 2019.

What force of nature kills more New Zealanders than volcanoes, tsunamis and earthquakes combined? Landslides. With climate change making landslides more frequent, and the South Island overdue for a big quake, scientists are racing to understand the risk. But the tricky part is translating that existential maths into action.

Behold the evolution of flowering plants, painstakingly put together by gene sequencing thousands of species, including some 200 from New Zealand. Scientists published the “tree of life” in Nature and say it can be used as a sort of periodic table for plants, or a roadmap for researchers working on conservation or new medicines, for example. “It’s like peering through a window across 150 million years of history,” says Kew Gardens’ William Baker, an evolutionary biologist who led the international project. “A kind of ‘family photo’ across the ages, made possible by the amazing molecular fossil record.” The scientists note a burst of “explosive diversification” early in the Mesozoic Era. Reptiles were on the rise and so were flowering plants, becoming drivers of large-scale planetary cycles such as climate and water. A second surge, in the Cenozoic, was possibly caused by a drop in global temperature, or by feedback loops between plants and insects, which were also diversifying rapidly. Even with close to 200 scientists working on this project, including all 330,000 species was out of reach. So the team plucked one per genus, leaving a bouquet of “only” 13,600 to work with. After eight years they’re about two-thirds of the way through.

A vicious strain of myrtle rust is burning through our bush. Dozens of native species—and the ecosystems they support—are at risk. Scientists think we have three, maybe four years before the biggest pōhutukawa start to fall. They’re racing to find a way to stop the rust—and to save seeds from plants we stand to lose forever.

Grass seeds. The waves that the tide etches in sand. Our own muscle cells. The stacked chambers of seashells. All of these, Hungarian and Belgian mathematicians say, are examples of an infinite class of shape they have just mathematically defined, and call “soft cells”. Imagine pinching a circle in two places, twisting it however you fancy, and letting go—you’re left with a curved shape that has two sharp corners. That’s a soft cell. Lead author Gábor Domokos has made a career out of noticing and naming the geometry of nature. As he and co-authors write in a new paper, the human quest to find “tilings”—ways to fill space with shapes that fit snugly together—began 10,000 years ago with the advent of masonry walls. Since then, we’ve focused on artificial shapes that have multiple sharp corners: triangles, squares, hexagons. But, they note, that nature has been tiling space for much longer than we have, and uses shapes that are curved, with “few, if any, sharp corners”.

Loading..

3

$1 trial for two weeks, thereafter $8.50 every two months, cancel any time

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Signed in as . Sign out

Ask your librarian to subscribe to this service next year. Alternatively, use a home network and buy a digital subscription—just $1/week...

Subscribe to our free newsletter for news and prizes